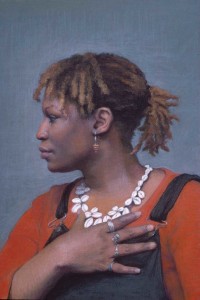

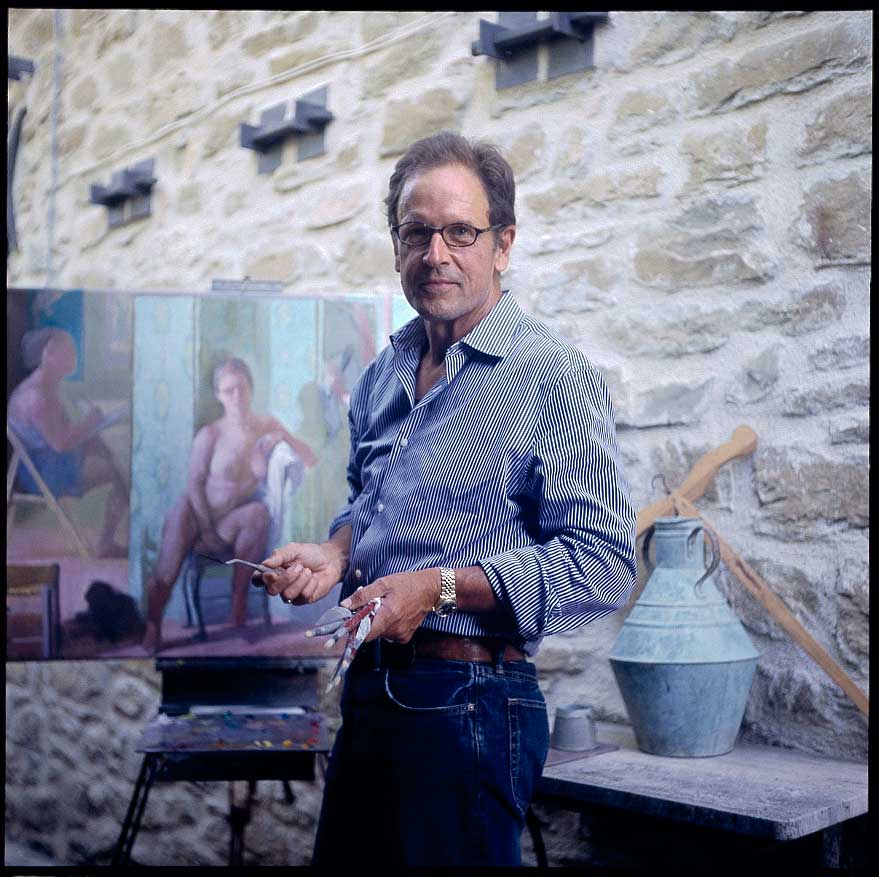

Photo credit: Jason Houston

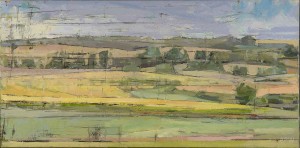

click here for larger view

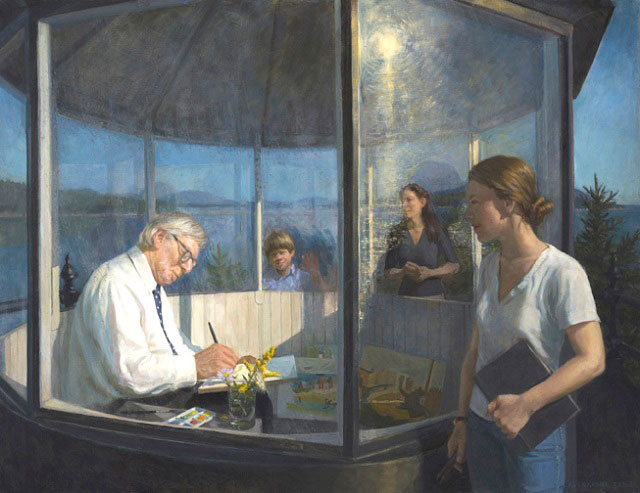

A’Dora Phillips interviews Lennart Anderson

in Collaboration with Brian Schumacher

Lennart Anderson on painting from life with central vision blindness; what vision loss has taught him about painting; art school; creativity; genius; influence; not fitting in; and hunkering down.

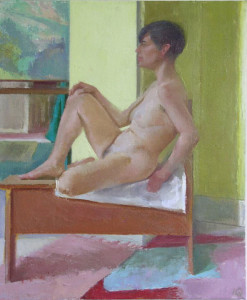

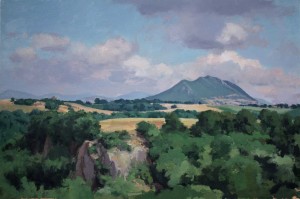

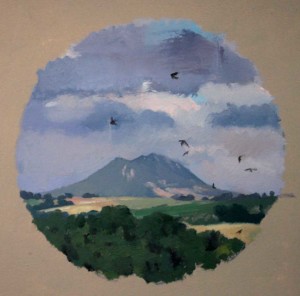

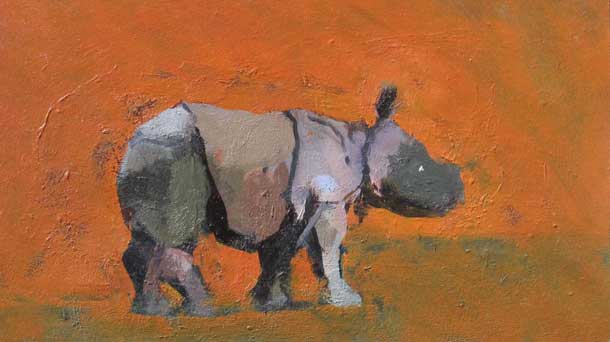

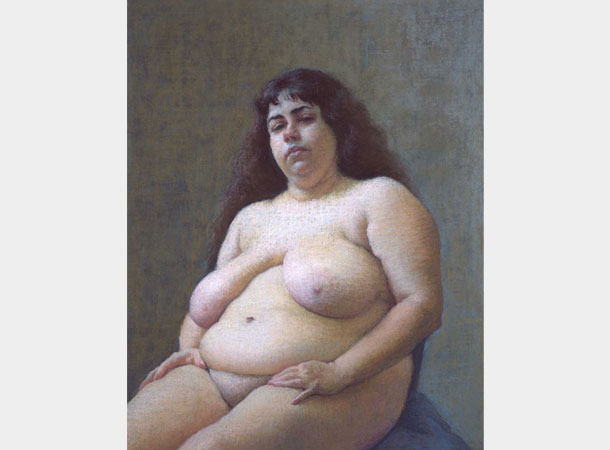

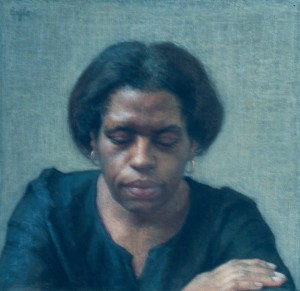

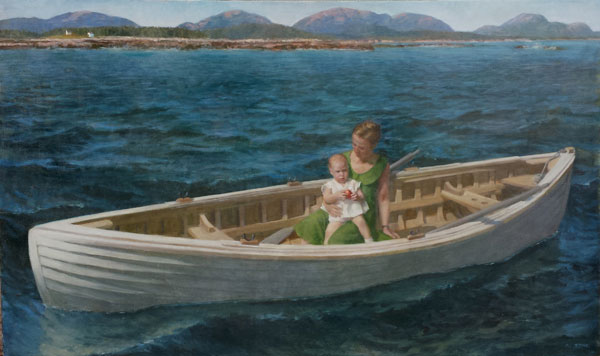

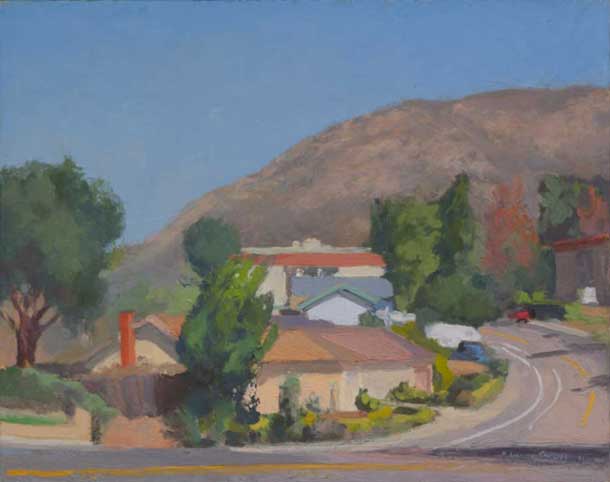

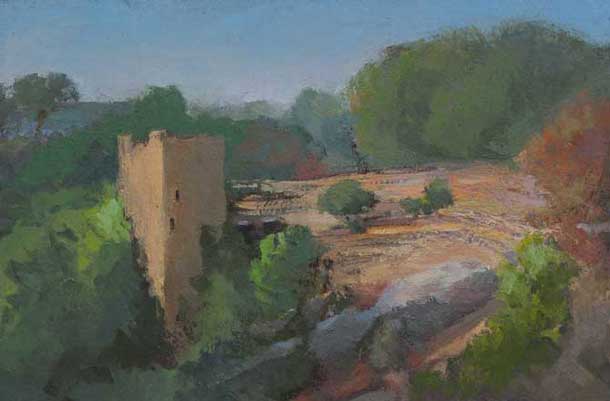

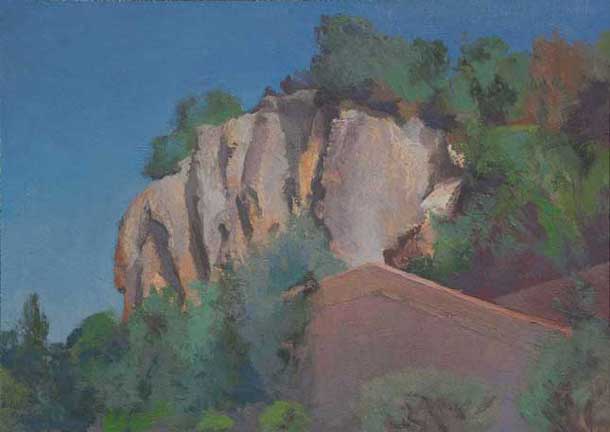

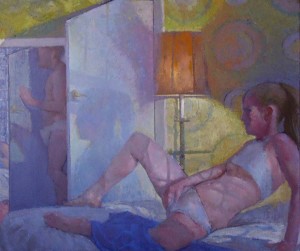

The perceptual painter Lennart Anderson, who turned eighty-five this summer, currently has a show on view of figure drawings and portrait paintings at Leigh Morse Fine Arts. Several of the works in the show have been done in recent years, as Anderson faces the greatest challenge of his artistic career and struggles to paint with central vision blindness due to macular degeneration.

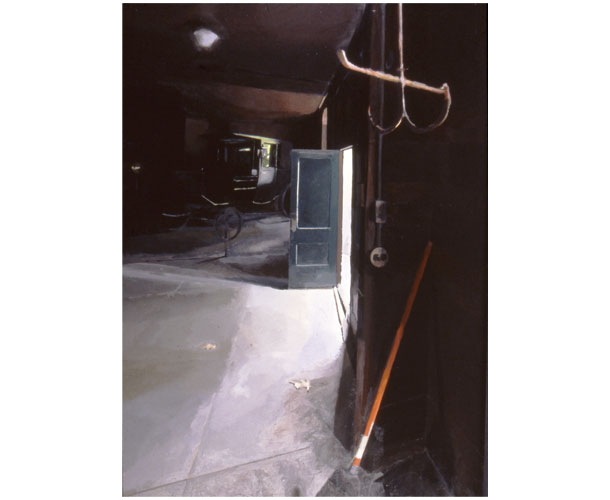

The disease struck his right eye in the late nineteen nineties, but for a few years, he was able to continue working with little trouble using the monocular vision that was left to him – partially because he’d always relied more on his left eye to paint. When his left eye succumbed to the disease in 2003, it was a different story. Within hours, he went from being able to see to having such a disorganized glimpse of reality that he doubted the solidity of the world around him. On direct glance, a gray spot stood between him and whatever he focused on. In addition, straight lines looked wavy, doorways appeared out of whack, and objects seemed smaller and farther away than they were. He could no longer read, recognize faces, perceive color, or put his finger down precisely on the spot he wanted.

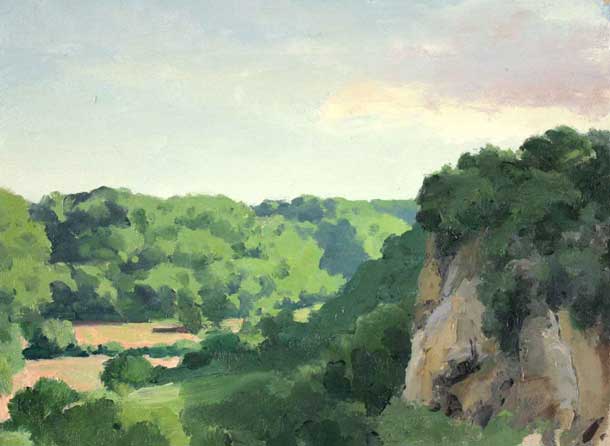

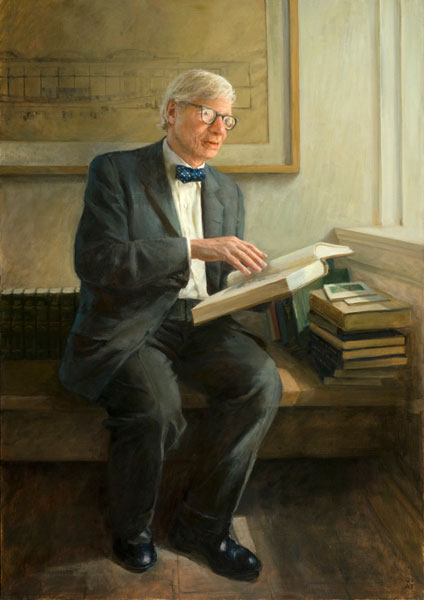

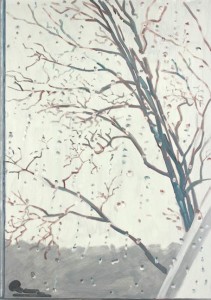

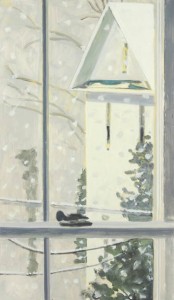

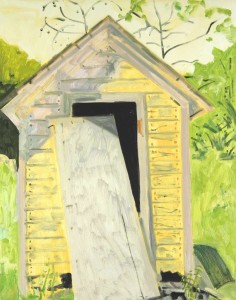

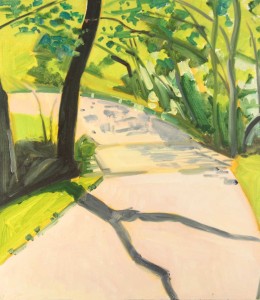

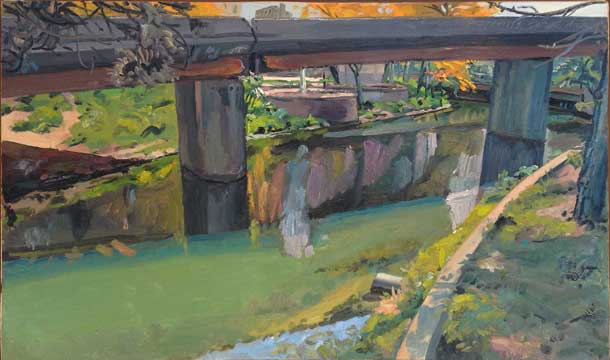

While Anderson has not read the New York Times since that day in 2003, he continues to paint, sometimes from direct observation, though more frequently from drawings he did when fully sighted. His painting techniques have necessarily evolved as his vision has deteriorated, but his daily ritual has changed little from what it has always been. By mid morning, he is in the third floor studio of his Park Slope Brownstone, classical music playing as he mixes paint. His work-in-progress waits, his palette, the monographs on Velazquez, Ingres, Degas, Poussin, and the many other artists who have influenced him. He has worked in the same third floor studio since 1966, and a collection of objects reveals the passing decades: catalogs from shows long past, drawings and notes composed by his children when they were young, sketches and photographs of Anderson’s late wife, Barbara. His studio’s most recent additions include accouterments related to vision loss: a magnifying glass on top of his Ingres monograph, a magnification machine, a big button phone, rulers and bits of paper with mathematical calculations on them, which he uses in preparation for transferring a gridded drawing to his canvas.

Some of what Anderson has painted this past decade is undoubtedly among his strongest work, though decidedly different from what he did before suffering from macular degeneration.

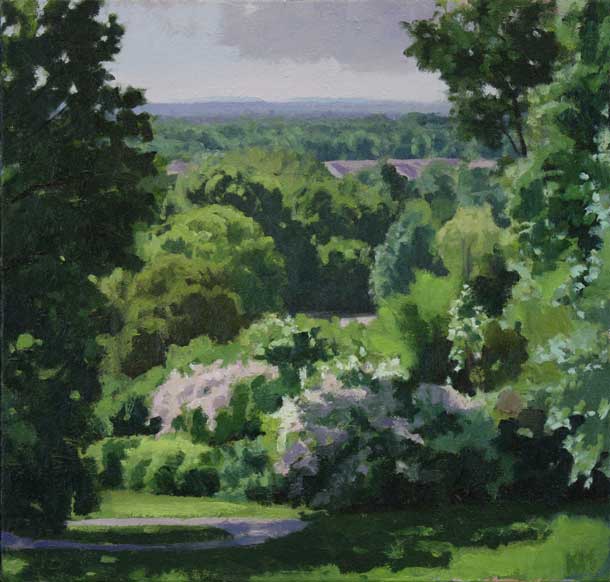

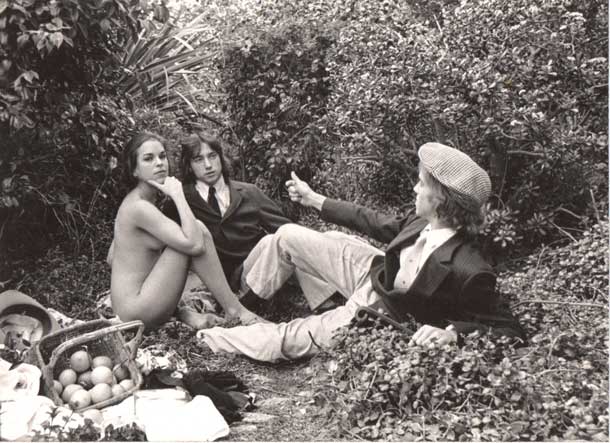

Brian Schumacher and I spoke with Lennart Anderson at his Park Slope studio on several occasions between January 2012 and July 2013 and were joined by the photographer Jason Houston on June 22, 2012. We found on our first visit to Anderson’s studio one of the walls dominated by “Idyll III”, a painting Anderson had been working on for more than thirty years. We were amazed by Anderson’s determination to finish as a legally blind artist a painting he had started two decades before, especially as he described how erratic his vision was and the problems this created for him as a painter. He persevered, however, and “Idyll III” served as the centerpiece of Anderson’s March 2012 exhibition at Leigh Morse Fine Arts (which Jed Perl of the New Republic cited as one of the year’s top three gallery shows). Over the past year and a half, Anderson has moved on to a composition of three figures on a bluff, based on drawings he has gridded and transferred. He has also been painting portraits from life. We have talked with him about his drive to work from life, the painting challenges that come with diminished vision, how to use the inspiration you get from other painters, and what it was like coming to New York City as a young artist in the nineteen fifties.

VISION LOSS & LOOKING

A’DORA PHILLIPS: You have been legally blind due to macular degeneration for the past decade, but are still painting. This must mean you are still able to see to some degree?

LENNART ANDERSON: What I see is erratic and very hard to describe. I can’t say I’m blind, but, when it comes down to it, I don’t see well. That’s why reading is so damn hard. I have that blind spot. If I’m looking for something, I can’t find it. I have to look over and underneath and to the side. I think I make a lot of it with people. What are you asking for? Sympathy? I just want people to understand that, even though I can see, there is a problem – though I gather it’s pretty easy to spot that there is a problem. It’s interesting, for instance, how quickly people will give me a seat when I get on the subway – right away, usually. But, I’m old, really old. And maybe it’s that. Maybe people don’t even notice that I’m blind. That I’m having trouble seeing.

To keep my eyes from worsening, I get an injection every seven or eight weeks. When I go in to the doctor’s office, they always do the same thing. They have me sit down, and they project letters on to the screen. They always start with the letter E, and I can’t see it. Every time I go there, the same thing. So, they try the next one. But my eyes haven’t really changed – or I don’t think they have – since the summer of 2003, when within a few hours I went from seeing well to not being able to make sense of things.

Because of my vision, I’m using my life now when I paint. I mean by that, all the painting that I’ve ever done.

PHILLIPS: I notice you have a stack of books here, with a magnifying glass. Are you able to take in a whole painting or drawing now from a book or do you have to look at it in pieces?

ANDERSON: I live on books. They’re the greatest things. Before my eyes went bad, and I would take out my book on Velázquez every evening and pore over his paintings. I was learning, but I wasn’t studying. It was coming in from another place. Now, I can’t see the images in books much at all, but I still pore over them. I know the paintings so well that I imagine I’m seeing them, but I don’t really see them.

PHILLIPS: Despite your vision loss, you paint in your studio nearly every day. What is your working day like?

ANDERSON: I get up early and come up here and procrastinate. Often, I just listen to music and don’t do anything until about two and the light is going to go. Then, I might work for an hour or two. That’s to save myself. But that has always been my habit. When I was painting in the nineteen fifties, I would sometimes find myself going through some job lot five blocks from my house, when I was supposed to be working. After supper I would start to paint, because I did not want to lose the whole day. It’s always been that way. Unless I have someone posing for me.

PHILLIPS: Habits aside, you have gotten a lot of painting done since 2003 and have had two shows, one in 2008 and one in 2012.

ANDERSON: Yes. And all the paintings in my 2008 show were done after macular degeneration. Most people are surprised that I’m working. Are you still painting? What else would I be doing?

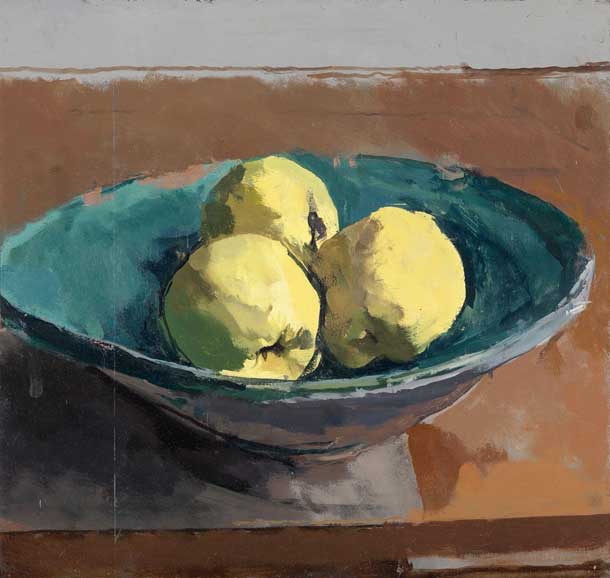

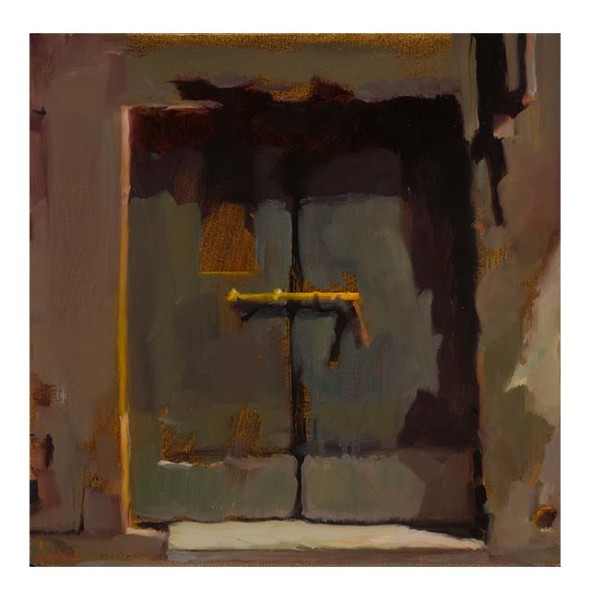

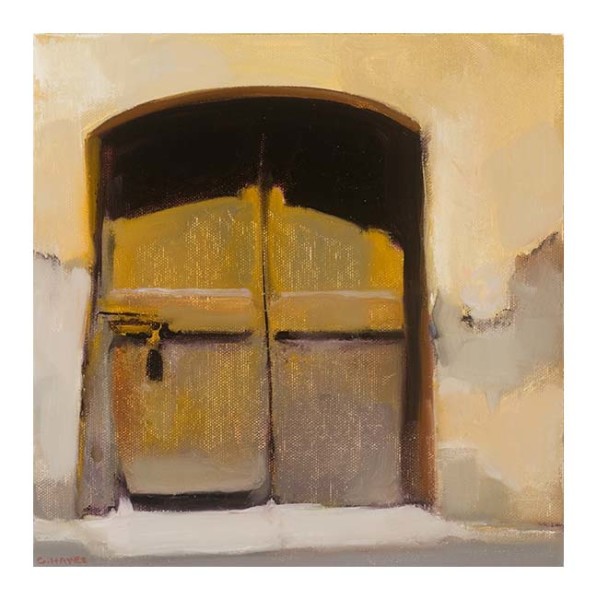

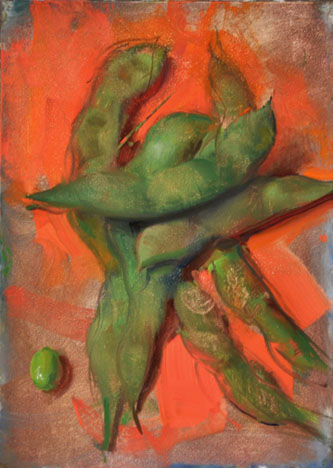

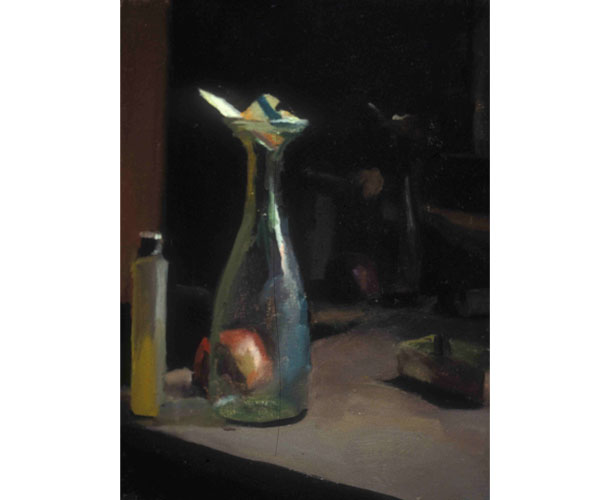

PHILLIPS: Up to when you lost central vision, you painted detailed still lifes from direct observation, along with figures and portraits. In the first few years after your eyes went, you did a few more still lifes of a lion’s mask, and they are entirely different from what preceded them. Did you have to modify your painting process significantly to complete your lion’s mask paintings? Did you work from direct observation, as you typically had?

Lion’s Mask, 2006, Anderson’s last still life painting

ANDERSON: I did three paintings of the lion’s mask. I painted it once with a tiger plant and once with an artichoke up in Maine the summer after my eyes went. In fact, I took the mask with me to Maine precisely to paint it, since it’s nice to know what you’re going to do, instead of hanging around and worrying about it. The third painting, the one with the simple head on it, I did later, in my Park Slope studio.

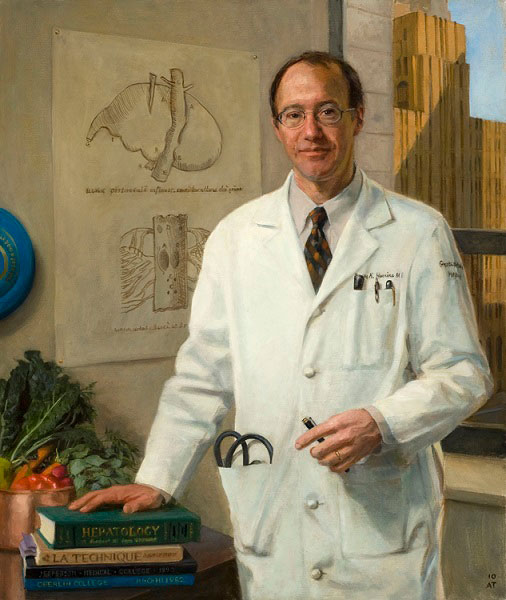

When I painted the lion’s mask in Maine, I used photos, a very difficult decision for me. I had always hated the thought of depending on photographs, since you’re not painting the subject, you’re painting a photo. But, honestly, a damn photo is better than your eyes, even if you can see. I always knew that, but I didn’t want to cave in. People say, ‘photos lie,’ but that’s bullshit. I never painted a better head than Bart Giamatti’s: for weeks, I drove to Yale and spent Sundays in his office, trying to paint him while he was watching football. I could never get it going. Then, at some point, a photographer went in to take some pictures of him. I asked to have some of the photos and used them to finish the portrait in my studio. With “Lion’s Mask,” I didn’t rely on photos entirely, though. I also had the mask very close to me. So I referred both to photographs and the mask as I painted.

Later, back in Brooklyn, I set the mask up again, right next to me – it had to be close for me to see it. There’s no stepping back now to see something better; if I step back, I lose sight of something altogether. When I painted the mask in Brooklyn, I tried to do so without using a photograph as an aid. I wanted to just try painting it from direct observation, but without my realizing, the image would slip away from where I put it on the canvas by a quarter of an inch or so. The more I worked on it, the more it would go off. Rita Natarova, a painter and former student of mine, was living with us [Anderson and his daughter] at the time, and she would help me correct the drawing when I couldn’t control it and it shifted. It was quite an effort. I have the same problem now. When I try to paint the blue around the figure in the painting I’m working on right now, I think I’m painting right next to the figure, but in the end, there’s a faint halo around it.

You see, it is hard for me to paint with my eyes in the condition they are in right now for a number of reasons. I can’t even see some points that are close together. I can’t put my hand down where I want to. I can’t make a line where I want to. When I can’t put something down where I think I’m putting it, it’s off. Then, you have to correct. I can’t work with a full brush. I don’t have confidence in it. You can’t see it so you don’t know if it’s right. It’s bad enough when you can see!

PHILLIPS: The lion’s mask paintings are your last still lifes after a lifetime of still life painting. Did you abandon still life because it was too hard to see the subject?

ANDERSON: That’s right. I can’t see a still life. Like, the apples over there on the mantelpiece, I can’t really see them. I know them well enough that I could paint them from memory, but that’s not what I do.

PHILLIPS: Do you work from direct observation anymore?

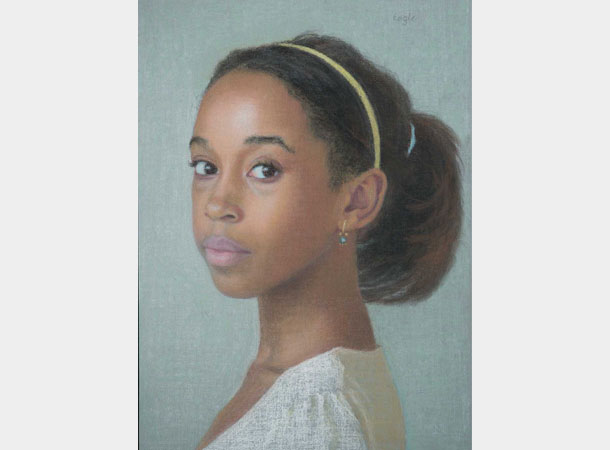

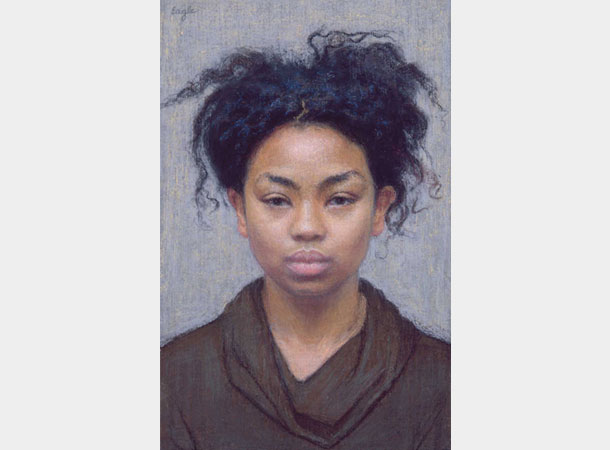

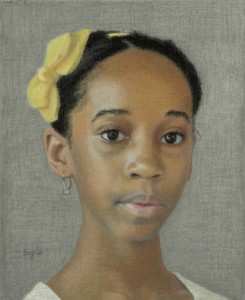

ANDERSON: I still have people sit for me sometimes. I put them through hell. I tried to do a head of a beautiful girl, Dali-lah, we call her. Delilah is her name. Dali-lah. It would have worked out had I had the confidence.

PHILLIPS: You started to lose confidence in what you were doing?

ANDERSON: I don’t know how I can beat that. If you can see, that’s good, but if you can’t see, you have to hope that the painting is going well. I kept changing my painting. It was much further along at one point.

Maybe the most significant problem I now have with painting – and this definitely makes it harder to do a portrait – is that I have a difficult time painting back to front. In the old days, I would have put in the big form that the eyebrows sit on before painting the eyebrows themselves – which involves working more comprehensively. But I can’t paint through the eyebrows anymore because if I did they would be lost.

I try to set things up so that I can work in a broad way if I can. I try to work with a bigger brush. Not get into this tiny stuff. I can actually paint better with a bigger brush than if I was into the small brush. I can just get a feel for the gesture of the form. And that helps.

PHILLIPS: Is that because there’s a memory in the hand about the gesture of the form?

ANDERSON: It may be. That’s probably true to how I feel.

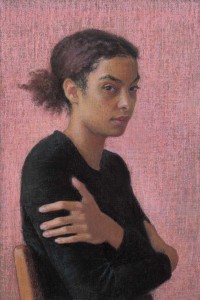

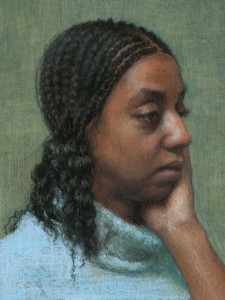

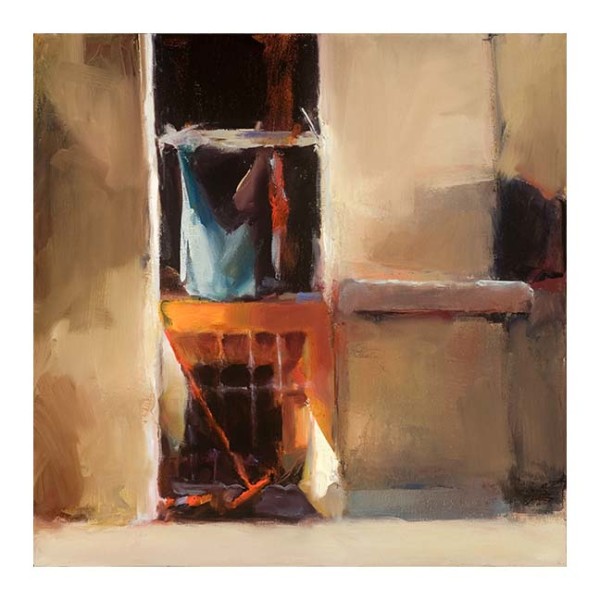

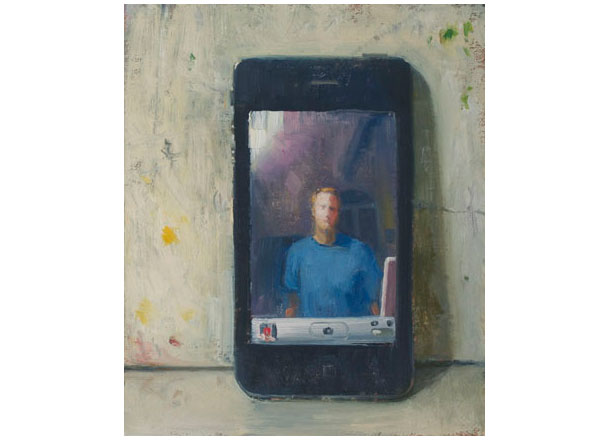

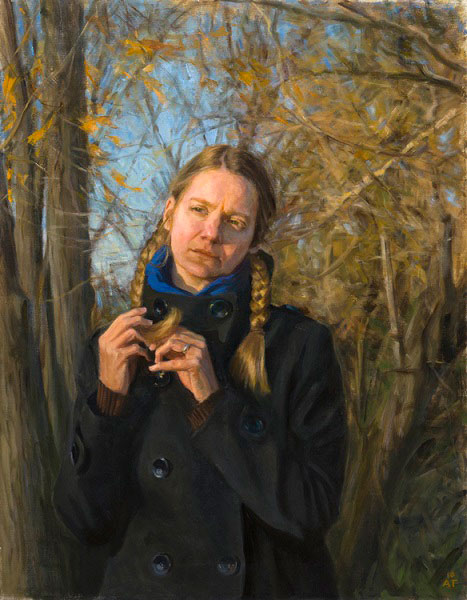

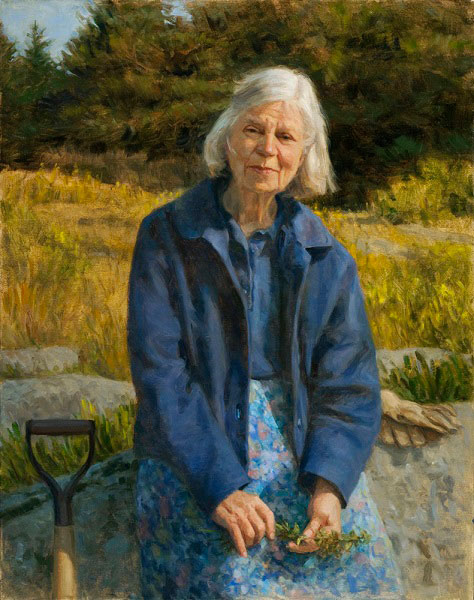

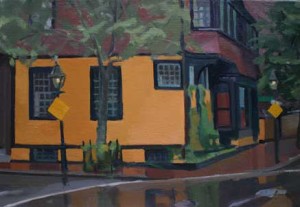

Portrait of Rita Natarova, 2013, as shot in February 2013

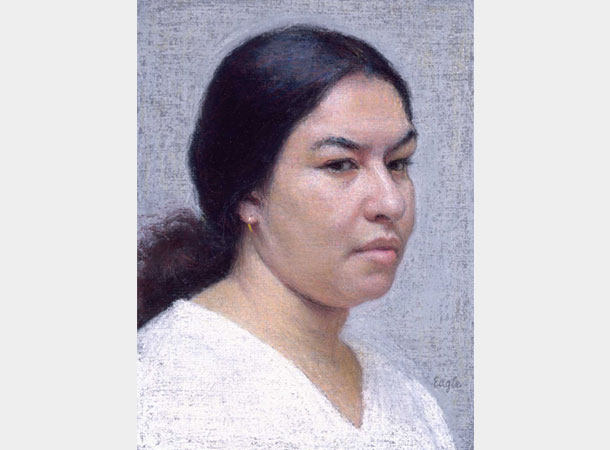

PHILLIPS: After working on Delilah’s portrait, you undertook one of Rita. Do you essentially follow the same process as before macular degeneration when you set out to paint a portrait, as regards having the model sit for you and painting from observation?

ANDERSON: I could never paint a head the way I used to, often in a single sitting, with the subject at a distance. I can’t see anybody. It’s just my bullheadedness that makes me try. That’s what it is. Straight out bullheadedness. Wanting to paint a beautiful woman. Wanting to do a great head, not one you have to make allowances for, but a head that will really knock people out.

Sometimes, I had to be within inches of Rita when I was painting her. The drawing was constantly changing. She would tire and couldn’t hold the pose and, like with “Lion’s Mask,” I couldn’t keep my drawing steady on the canvas. With these two things moving around, the shape of her head kept changing. Every day, a different shape, but it still looked like her. This went on for weeks. She must have sat for me twenty or twenty five times. I never got into the features while she was posing; by the time our painting sessions ended when she left for London, I still hadn’t put in the eyes and mouth. I remembered the shape of her mouth one day – it was something I could keep in my head – and put it in from memory, as well as the eyes. She thought she would have to come back to pose for me again at some point so that I could work on the features and was surprised when she saw her finished portrait on the Internet.

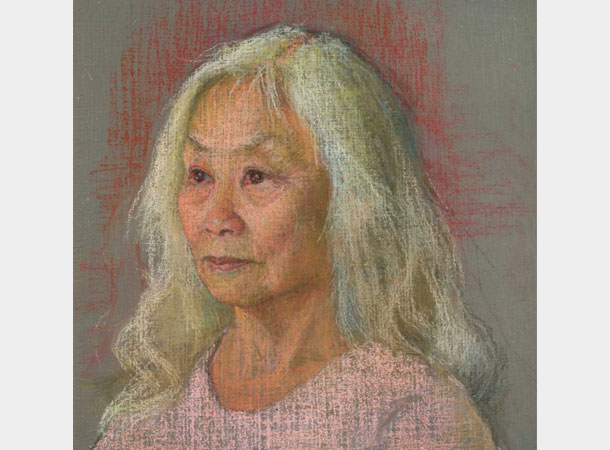

Now I’m working on a portrait of Kyle Staver, who has a unique head. The problem with that is that you have to be able to see well. I can’t fake it or paint from expectation. I have to rub noses with her, literally. It’s really terrible. With my magnifying glass. And even with a magnifying glass, I can’t compare two points. It’s very frustrating, because that’s what you paint with – similarities and differences.

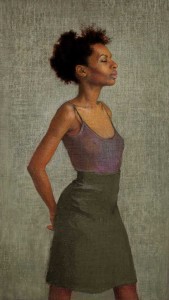

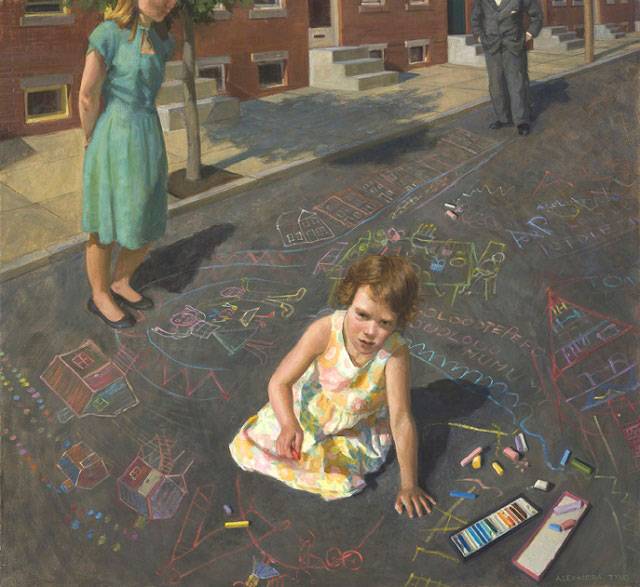

PHILLIPS: Aside from the occasional portrait, you work mainly work from drawings now.

ANDERSON: That’s right. When I returned to New York from Maine the summer I lost my sight, I decided to see if I could make painting from the drawings I had done of models. I have a lot of figure drawings from when I drew with my students on Saturday mornings at Brooklyn College. I treat the drawing as if it were the model, which relates back to one of the things I used to emphasize when I taught – that you don’t have to make drawings, unless you won’t have the model to work from later. Sometimes in class, I would see a student making a drawing, and the drawing would be terrible, but they would be planning to paint what was in it, because they felt they needed to stay true to what they’d put down. Don’t use the drawing. There’s the model. That’s your drawing. You don’t make something in between you and it.

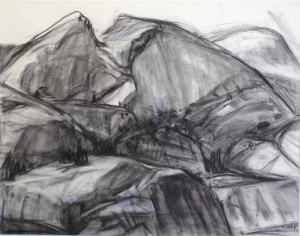

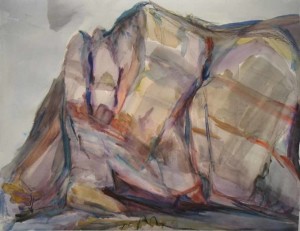

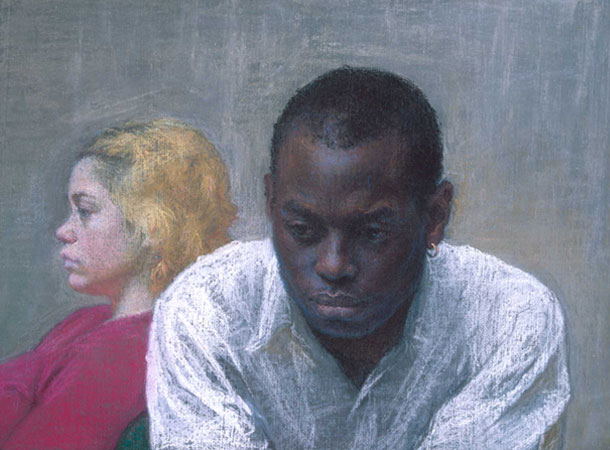

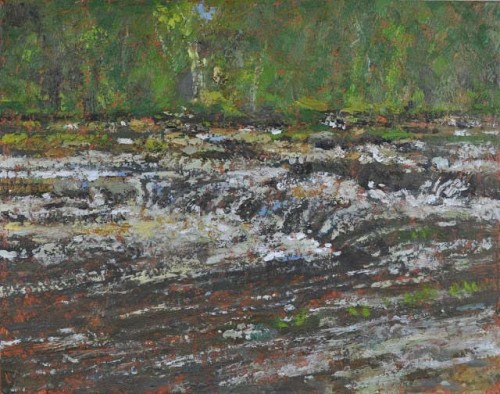

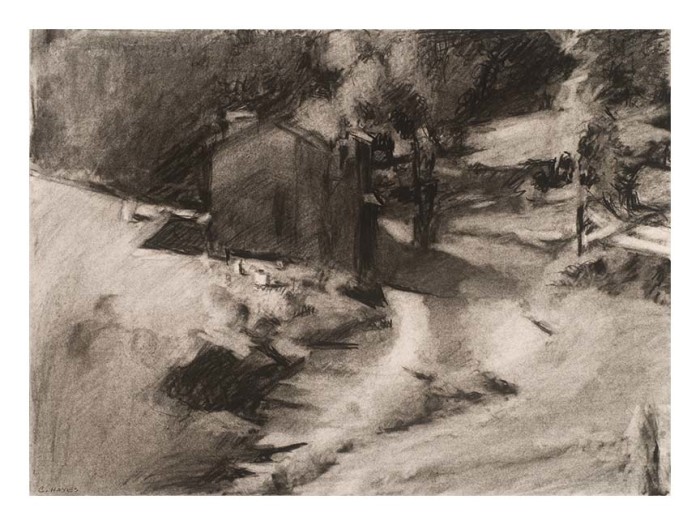

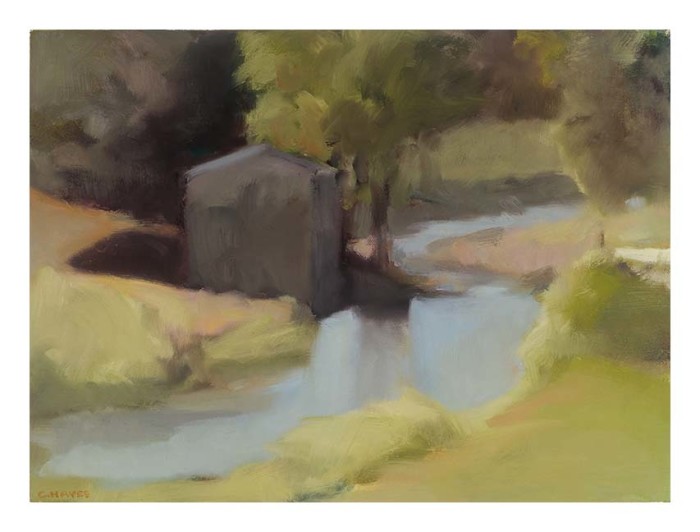

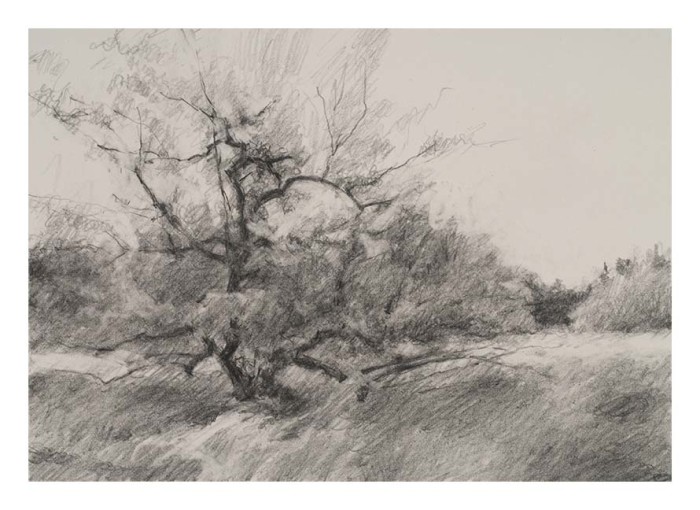

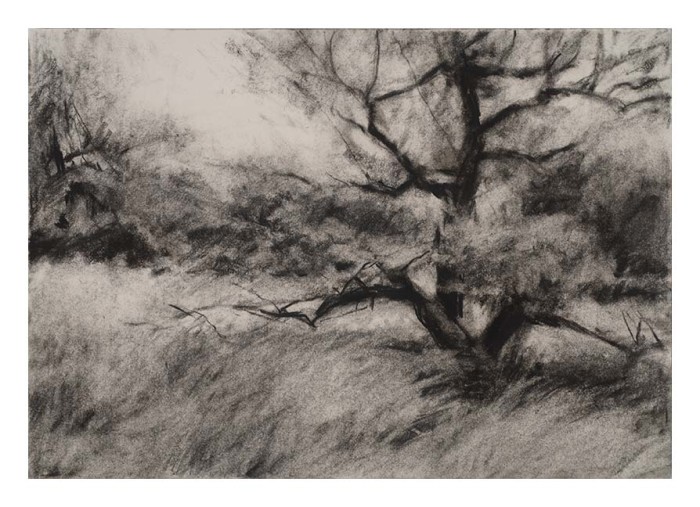

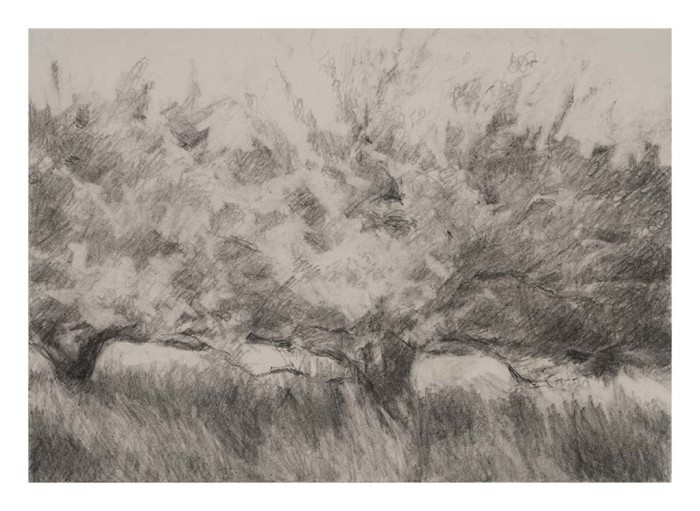

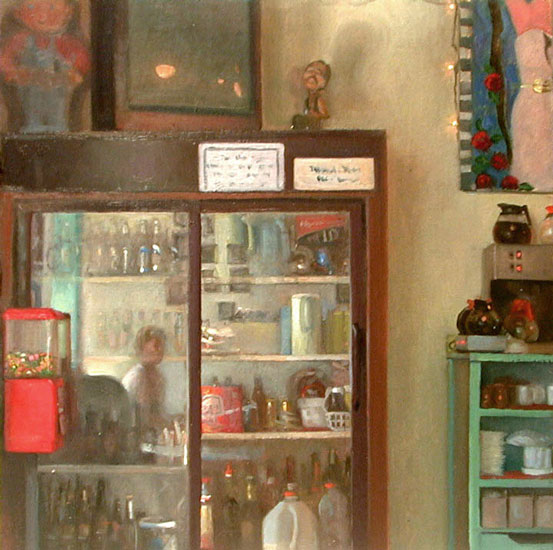

Some of the figure drawings Anderson has in his files and now works from.

Photo credit: Jason Houston

Because I’ve been working from my drawings, I’ll tell you, I’m constantly amazed by them. They don’t look like a whole lot, but then you start to analyze them in order to paint from them. The subtlety in them is mind-boggling. None of them took more than twenty minutes and some of the best ones took ten, but there’s a great deal of information included in all of them.

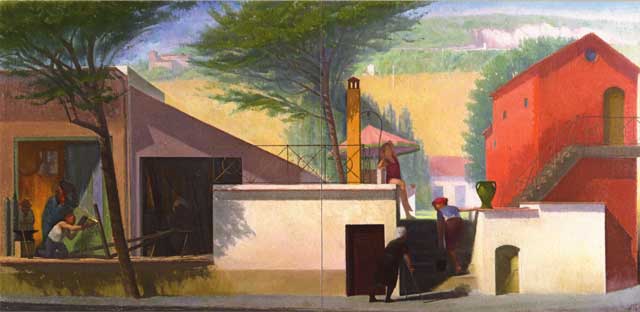

The big painting of Jupiter was the first painting I worked on using my drawings – an awful thing to have done so soon.

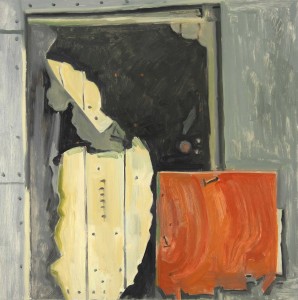

Jupiter and Antiope, 2004/5, the first painting Anderson undertook after losing central vision in 2003, using drawings he had done from the model pre-macular degeneration for reference.

A photocopy of the drawing that Anderson used as a model for Antiope in his painting “Jupiter and Antiope”

Anderson’s Study for “Jupiter and Antiope,”

PHILLIPS: What sort of painting process do you follow when you use your drawings as models?

ANDERSON: When I compose my paintings, I pull the figures from individual drawings that had nothing to do with one another.

I start by Xeroxing the drawings I’m working with – which I learned I had to do after screwing one up. Then I decide where it should go on the canvas, and divide the drawing in half, which gives me three points – having three points has always been crucial to me. After dividing the drawing in half, I take quarters, and so on, creating a grid that will allow me to transfer the essential lines of the drawing to the canvas. I go to a great deal of effort with the grid, trying to map out the drawings accurately. Not infrequently, there are three or four lines on top of each other, and I have to choose between them. I sometimes make mistakes, since marks that may not look like anything, or that might even seem like mistakes, turn out to be meaningful and descriptive. I try to keep the mathematics as simple as possible, but it gets kind of horrible sometimes.

The drawing Anderson used as a model for Antiope, gridded

PHILLIPS: So you use the grid to control a sense of scale and as a way to transfer the movement of the lines, right?

ANDERSON: The grid is the master. I don’t fool around with it. It can be murder trying to paint what is in a line. It’s harder to paint from a drawing than it is from life, by far. Though, of course, painting from a drawing now in my situation is not what it would have been.

One of the reasons it is so hard for me to work this way is because you have to keep telling it what it is, you know? One of my main tenets has always been: Don’t tell it what it is; ask it. That’s what I always told my students. But I can’t ask it anymore, and I often have to go on what I remember.

The irony is that because of working with the drawings – like in that painting – my painting is tighter than it has ever been before, more precise, when you’d think it would get sloppier. It’s all on that edge of how many sixteenths or thirty-secondths of an inch it is. In fact, I mentioned to someone recently that these days, my line is actually closer to an Ingres line than ever before.

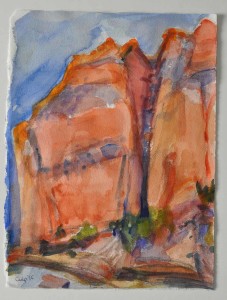

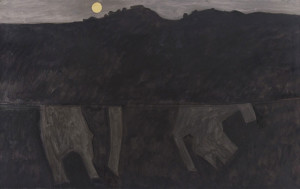

“Still life with salami and olive,” one of Anderson’s last still lifes before his second eye succumbed to macular degeneration.

PHILLIPS: You seem to work from a much more limited palette than you used to. Does that relate to your vision, as well?

ANDERSON: I don’t see color very well and have limited my palette accordingly. I understand what the few colors I use can do, and I don’t vary how I use them. Even so, mixing colors is very difficult. Yesterday, I mixed up something for the flesh tone – white and ochre, a little black to darken it. I left the pile of yellow ochre on my palette, next to what I’d mixed. I got my brush into the ochre, and it ended up on the painting, but I didn’t see it for a long time.

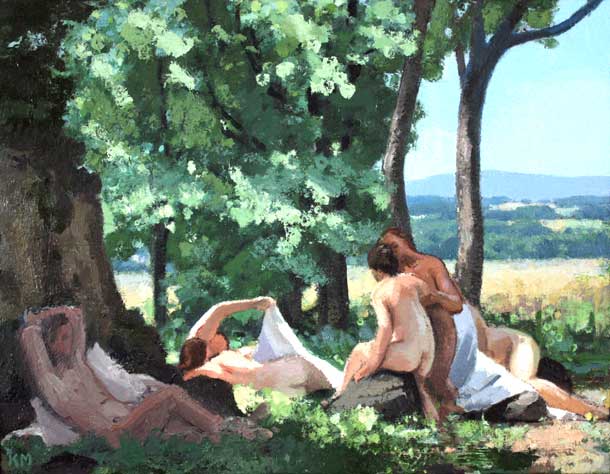

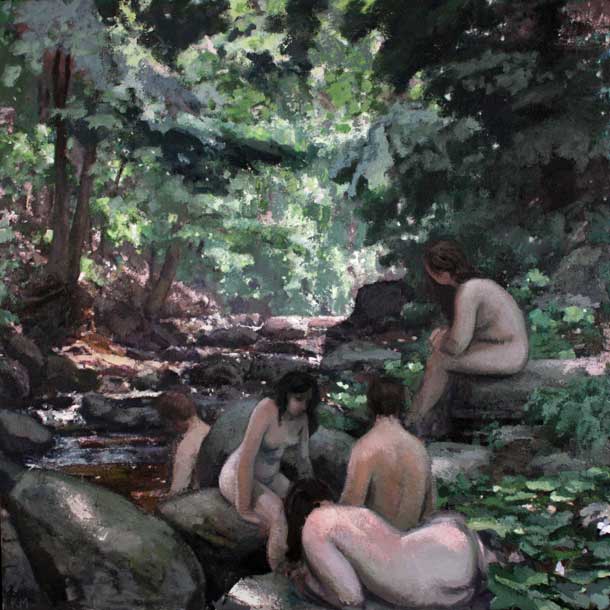

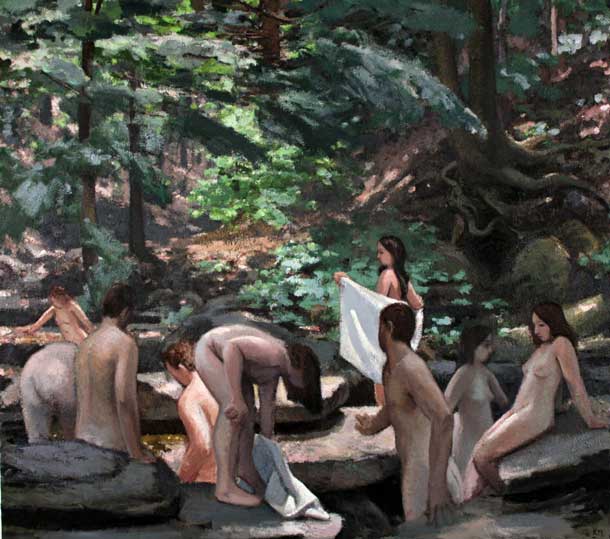

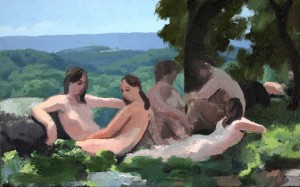

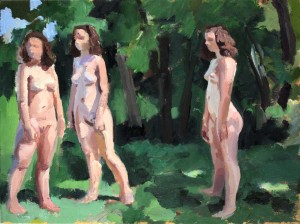

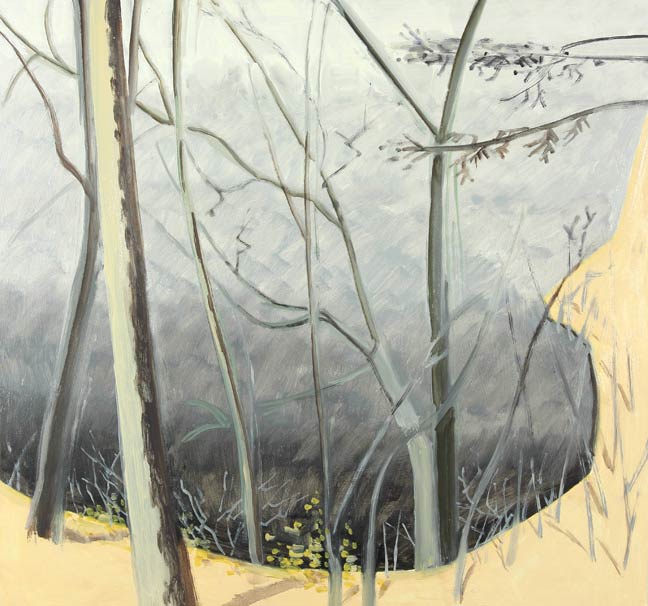

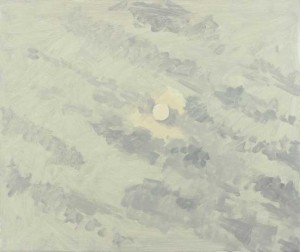

It occurred to me recently that I really ought to use a small painting palette now because I’m working with so few colors. The middle figure on my painting of “Three Nymphs on a Bluff” was essentially done with yellow ochre, white and black. Maybe some brown and raw sienna.

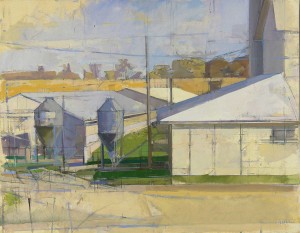

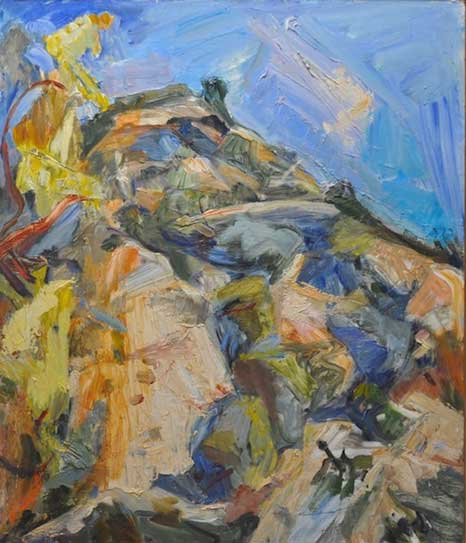

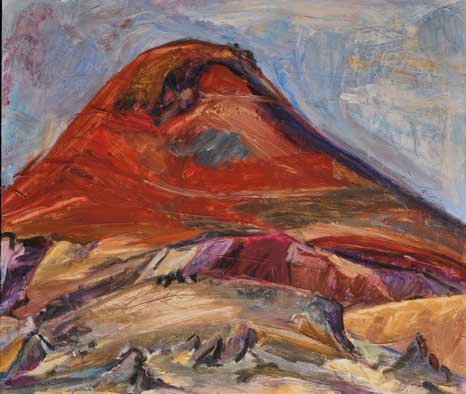

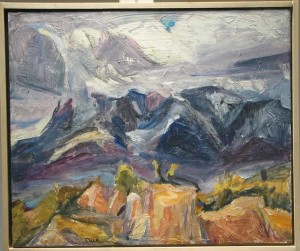

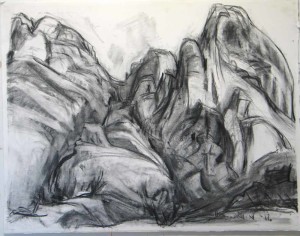

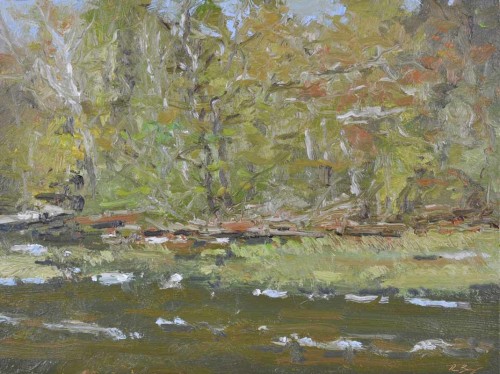

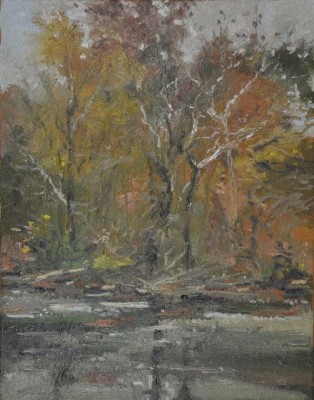

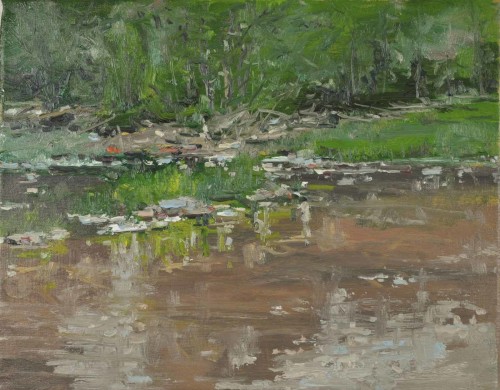

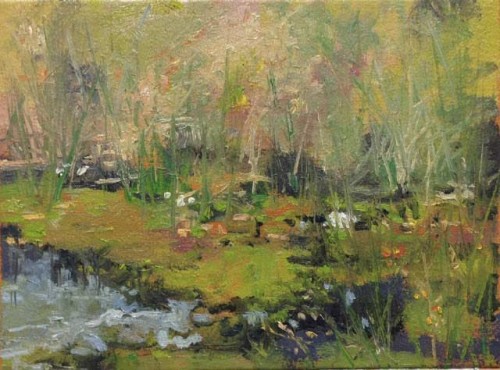

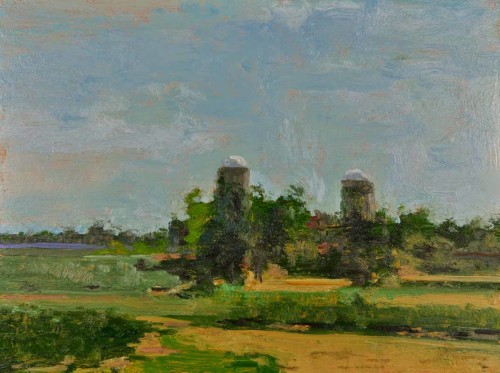

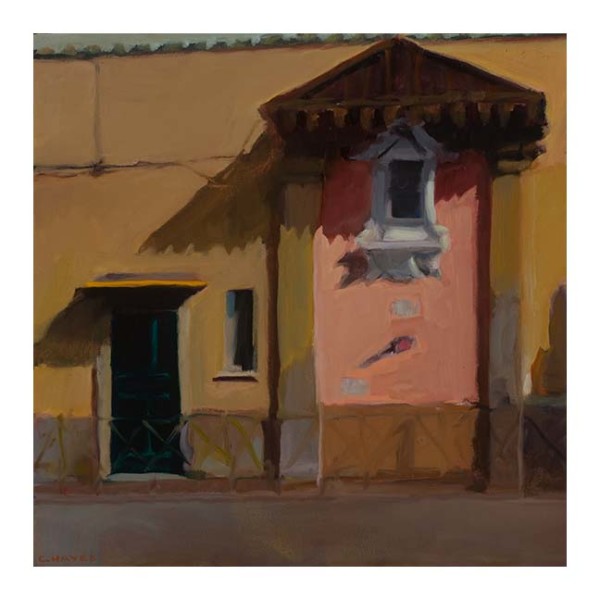

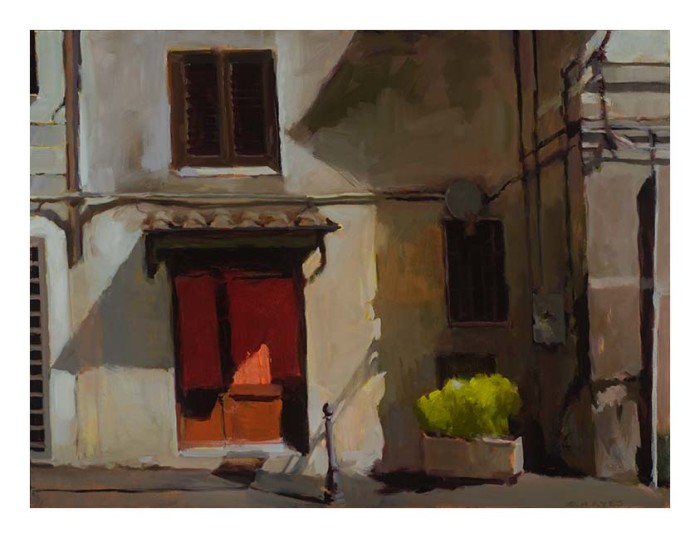

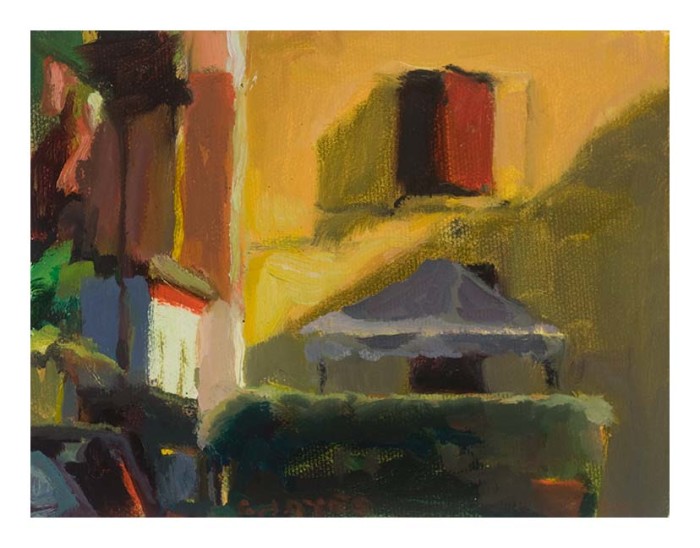

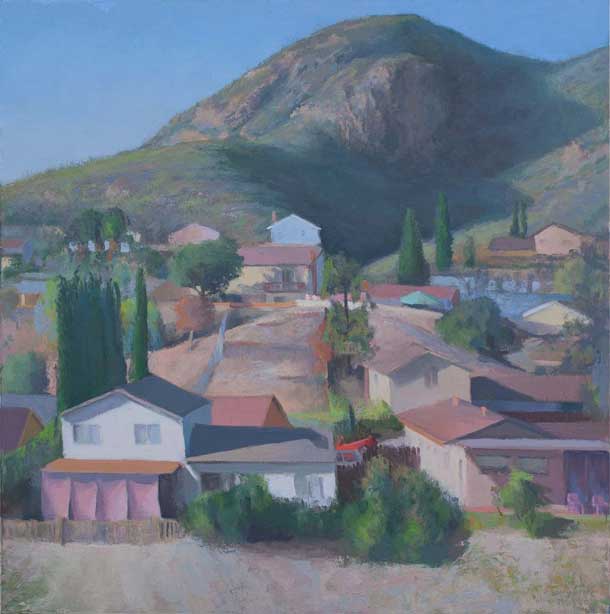

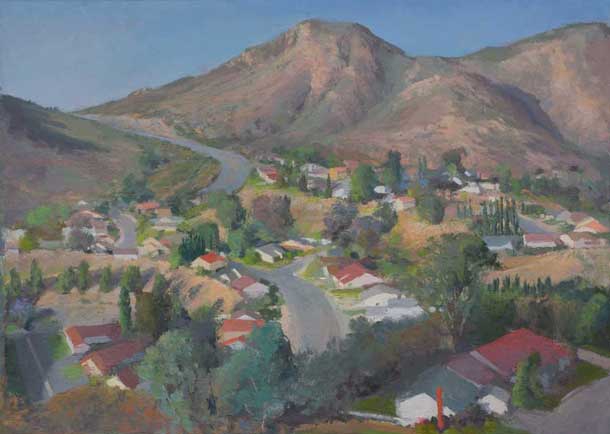

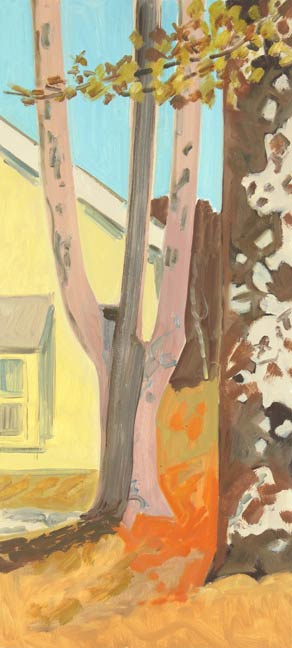

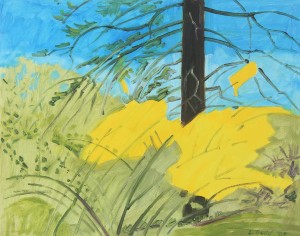

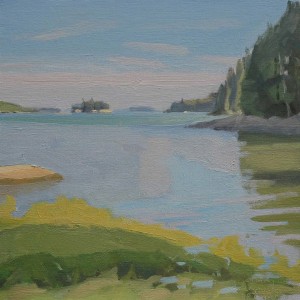

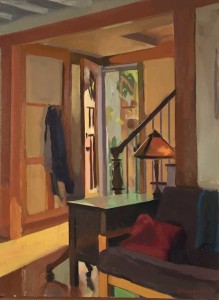

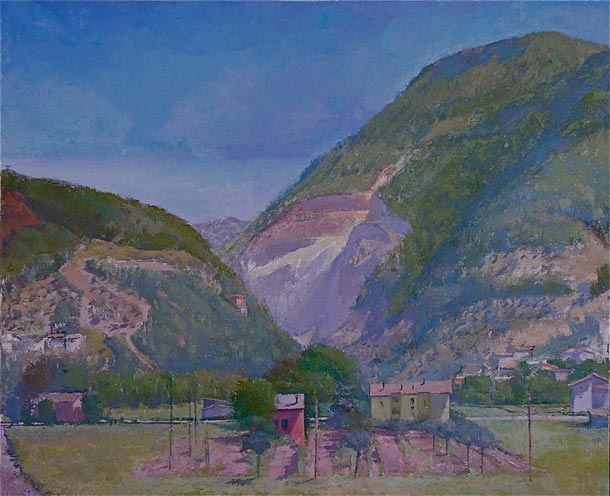

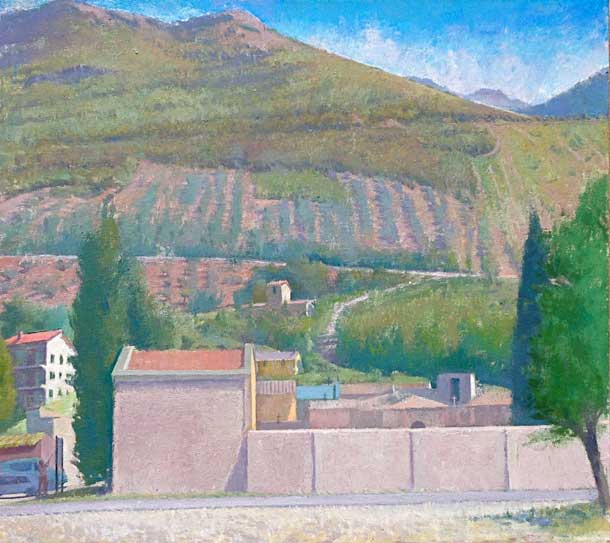

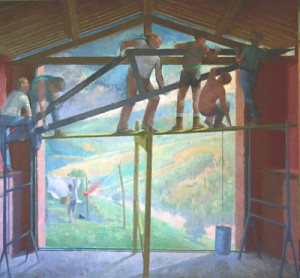

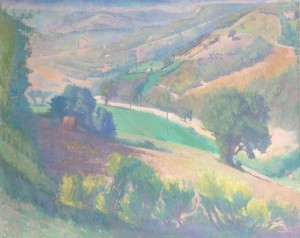

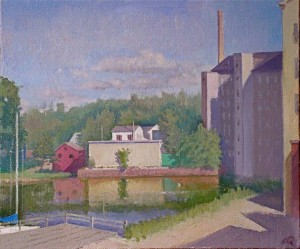

Above and below are two separate paintings Lennart has been working on since about January 2012 based on a composition of drawings, sometimes called by Anderson “The Three Graces” and sometimes called “Three Nymphs on a Bluff”. He was still in the process of working on them when these shots were taken, in February 2013.

I’ve learned a lot about painting from macular degeneration. Just yesterday, I had an observation about a painting of El Greco’s depicting an artist with a small palette in his hand. What the heck is he doing with such a small palette? That guy’s small palette really tells you something. The painter is not going to work on the whole painting, but just in one small area. There were probably one or two colors on his palette all together. Or, look at the dress in Ingres’s portrait of Princess Albert de Broglie. It was painted with Prussian blue, period. You know how dark Prussian blue is? It goes through the entire range. Ingres is not messing around with black or anything else. You see what a powerful thing it is to limit your palette. Historically, painters didn’t use color the way Cézanne or the other impressionists did. They screwed up color terribly, I think. Made it much more complicated.

PHILLIPS: You have been influenced by Degas ever since you encountered the auction catalogs from the sale of Degas’s studio contents at a friend’s house back in the nineteen fifties. It’s now widely accepted that macular degeneration was also at the root of Degas’s eye troubles, though in Degas’s case, it was an early-onset form of the disease. A lot of your recent strategies for working are similar to Degas’s. For instance, as his eyesight worsened, he seems to have relied on photographic reference and began tracing over his drawings as a starting place for paintings, exploring multiple iterations of the same subject, much as you’ve done with the “Three Nymphs on a Bluff.” Were you thinking about Degas as you strategized about how to keep working?

ANDERSON: No, not really. Degas is complicated. I don’t know how he did it, and I don’t know what the state of his eyes was. He was complaining about them forever and didn’t paint for the last fifteen years of his life. That was probably the eyes, but he might have just said, ‘the hell with it!’

For myself, I just had to figure out some way I could keep going, that’s all. Like today, I wanted to quit. I said, ‘this is ridiculous, just ridiculous. I’m not doing anything but measuring and getting it all wrong and throwing myself on the floor.’

ANDERSON’S REFLECTIONS ON THE CRANBROOK ACADEMY, 10TH STREET IN THE NINETEEN FIFTIES, AND HIS OWN PLACE IN THE ART WORLD

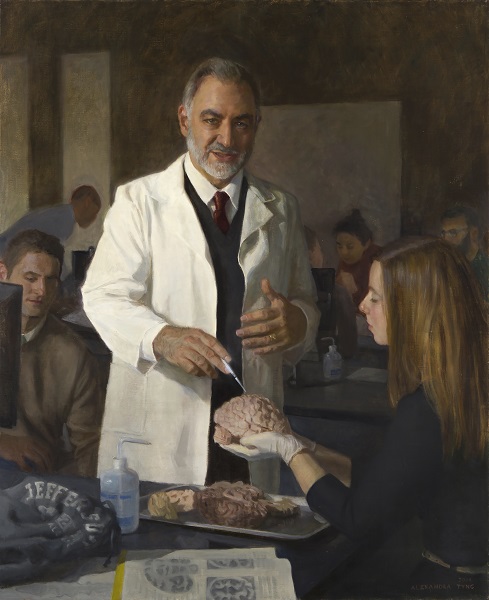

PHILLIPS: Changing direction somewhat, your drive to work from perception – that has been with you since you were in art school, if not before. As I understand it, you had to be somewhat bull-headed as a young artist in the nineteen fifties in order to pursue your interest in working from life. That includes when you were at The Cranbrook Academy, which touts itself as the cradle of American modernism and certainly aligned itself with the abstract expressionist movement when you were there.

ANDERSON: Even before I went to Cranbrook, when I was an undergraduate at the Art Institute of Chicago, they didn’t think much of things like likeness. Do a great head, you know, whatever that was and they all did some kind of thing, but it wasn’t a likeness. A good head in those days was a zero with a couple of lines in it. I left Chicago thinking I was an expressionist painter. After a time at Cranbrook, I found myself tiring of painting expressionist pictures. I started getting fellow students to pose for me and did portraits of them for $15 a piece. I was told not to paint the figure. But one day I saw the first model I’d ever drawn (in Detroit in 1943) at Cranbrook. Her name was Leona. She’d come out on the bus and was just sitting there. So I said, ‘why don’t I paint you?’ and I did.

Anderson holds his painting of Leona, done around 1951, when he was at the Cranbrook Academy.

Photo credit Jason Houston

PHILLIPS: Were you unique in that? Because that was definitely not a figurative period of time.

ANDERSON: I had friends who regarded me more highly than the faculty generally did. Even though I had a good final year at Cranbrook, I just slipped out. Nobody raved about my work except the sculpture teacher, who said I should stick with it.

It’s curious, though. The school wanted to show its breadth, so they used my painting of Leona in their catalog when I was there.

PHILLIPS: Why did you tire of expressionism?

ANDERSON: There’s a good answer to that. I’m not dependent on what I’m carrying around in my head. If you have something to look at, and if you’re diligent, and if you love it, you can make good art by working from perception. Otherwise, you think you have to have an idea. And then you paint your idea.

PHILLIPS: And why is it important, when you’re working from perception, to strive to represent what you see with a high degree of similitude? Why are you striving to do that even now, when it requires so much effort?

ANDERSON: I’ll give you a smart answer. Why do you play tennis with a net? You understand my answer, don’t you? It means you’ve done something right. That doesn’t mean copying, because you can’t do that, not well. You have to see and to organize.

PHILLIPS: So, you didn’t really have any training in figure and portraiture. You figured out how to work from life on your own?

ANDERSON: No. I’ve been looking at paintings forever. And I got a few pieces of advice early on that were crucial. For instance, I had a teacher in Chicago my first semester, Elmer Forsberg, and his mantra was that you had to draw the whole figure on the page. He had a way of doing so with circles, and I didn’t know of any good painter or good drawings with circles, so, I never adopted his technique, but I did get the whole figure on the page then and have ever since – when I wanted to.

I want to say something about the fact that I knew Pat Passlof at Cranbook. She was important to me. On the back of my expressionist canvases, she found the figure paintings I had done at the Art Institute of Chicago and liked them. That generated the representational direction for me.

PHILLIPS: But when you arrived in New York a few years later, you were still torn between working expressionistically versus representationally, weren’t you?

ANDERSON: When I came to New York, I had the idea that I wasn’t going to be an abstract expressionist, but it was the dominant style in those days and everybody – I shouldn’t say everybody, but almost everybody – was doing their version of it. And I was genuinely interested in de Kooning’s work, especially his early work, and what was behind the abstract expressionist movement. The abstract expressionists were there because they were fed up with representational painting – dark paintings, sentimentality. I thought I could do paintings that the expressionists could recognize. I met de Kooning and Franz Kline, though I wasn’t friendly with them. In fact, De Kooning visited my studio at the Academy in Rome when I was there, but he didn’t have much to say about my work, which disappointed me – unlike Philip Guston, who was excited by what I was doing. I knew Milton Resnick, as well, since his wife was Pat Passlof. Milton was a frightening man. He would scare you to death. Thought he knew everything. Once, when I visited Pat, I had a few small still lifes with me. Milton came in, looked at them, and said something like, ‘why are you doing these for?’ I said, ‘I’m trying to make a go of it, you know.’ And he said, ‘no, you’ve got to get with it and get on the bandwagon and take charge.’

But Pat made efforts on my behalf. She got me into the Artist’s Club, which was not easy to do, and I’d go there on Friday nights to listen to people talk about painting. And Elaine de Kooning once came to see my work when I was living on 10th Street and was encouraging. Before she left, she asked me what my rent was. I said, ‘$29.75′, and she bought a little wash from me for that amount. Later, when I needed a letter for the Rome Fellowship, she wrote one for me, though I don’t remember being the one to approach her about it.

Still, I’ll tell you, I was reclusive. I was in New York in the nineteen fifties, and knew a few people, but they weren’t the big names or anything like that. I lived on the same block as some of them for a year and a half – with Franz Kline and Willem de Kooning, and Esteban Vicente, and Milton Resnick. They are history, but I’m not history. It’s just the way I am. I’m not unfriendly, but I feel like I’ve always been hunkered down, you know? I’ve got something I want to do, or try to do, and am working to get by.

THE ARTISTIC PROCESS, GENIUS, AND INFLUENCE

PHILLIPS: I feel like, historically, artists have been much more able to move from imagination to observation, perception, and memory, that it all goes into the pot and is used. You’re one of the few contemporary artists I know who also seems to have embraced that path and move fluidly between different modes of art making.

ANDERSON: I don’t fit into anything very well. I didn’t deliberately do that. I just followed whatever I was interested in, painters and paintings that inspired me. I don’t claim to be one of those geniuses. You’re not supposed to be influenced. You’re supposed to be yourself, but I’ve always been influenced. Painters steal. Artists steal. I remember when I went to Cranbrook, I was so intimidated by the jargon about creativity. Creativity – I never knew what that was. I still don’t know. There it is.

Are you getting anything out of this – are you recording me?

PHILLIPS: Yeah. I am recording it. The recorder is right here.

ANDERSON: So, you’re getting material? Great. That is what I was hoping, that you were going to nail me down, ask the right questions, and make me talk. ‘Don’t tell it, ask it,’ as I used to tell my students.

A’Dora Phillips holds an MFA in Fiction Writing from the University of Massachusetts Amherst and studied painting for several years, including with Jacob Collins at The Water Street Atelier and Daniel Graves at The Florence Academy of Art.

Brian Schumacher is an artist and designer whose paintings and drawings are held in many private collections. He is also an Assistant Professor of Drawing and Design at the University of Cincinnati College of Design, Architecture, Art and Planning Brian has studied, taught and practiced traditional drawing and painting for over a decade.

This article has been written with the generous assistance of the American Macular Degeneration Foundation (AMDF), which is committed to the prevention and cure of macular degeneration and offers hope and support to the afflicted and their families: http://www.macular.org/

###

Painting Perceptions would like to thank A’Dora Philips and Brian Schumacher for their generosity in making this fabulous and important interview available to our readers. Additionally we wish to thank the American Macular Degeneration Foundation who has provided invaluable financial support for the professional photography and the many other expenses related to this project. They are also providing support for a planned film related to this issue, more information will be made available as we know more. They’ve given the art world a huge gift with this interview and artists should return their support as much as possible with their donations.

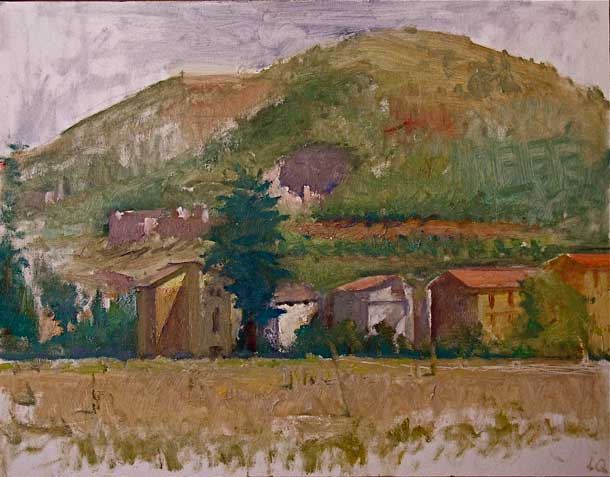

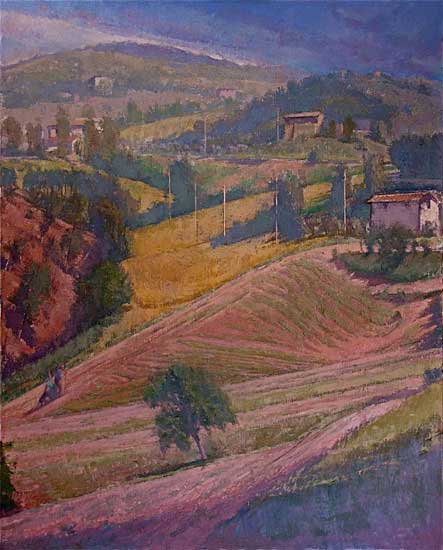

A previous Painting Perceptions article that includes a slide talk Lennart Anderson gave in Italy can be seen from this link.

A website dedicated to the work of Lennart Anderson as well as essay’s and interviews can be seen from this link – lennartanderson.com

.

.